Jake Ruttenberg, Greta Zableckas, Ryan Rogers: Our

Trash’s Future at DU

Since

beginning our enrollment here at The University of Denver it has been clear to

us that this school prides itself on being environmentally friendly. However,

after conducting our trash audit we have learned that the vast majority of DU’s

efforts of being sustainable are in vain. Either trash is finding its way into

the compost and recycling, in turn contaminating it, or the compost and

recycling is simply being thrown away with the rest of the trash. As a result,

our approximate 61% recycle and compost potential is nearly impossible to

achieve. Our proposal for change is two-fold. First, as with most issues,

proper education is vital. Secondly, we need to make the topic of trash,

recycling and compost more visible and prevalent. When both criteria are met,

DU can truly live up to its standard of being green and become a role model for

other schools and communities to follow.

Identifying our Problem:

Al Gore was one of the first people that really

brought to light the issue of the way we treat our planet. “The warnings about global warming have been extremely clear

for a long time. We are facing a global climate crisis. It is deepening. We are

entering a period of consequences.” As such, it is our responsibility as not

only inhabitants of this planet, but as students of this university to do all

we can in avoiding the point of no return he so often speaks of. One of the

leading causes of global warming is the emission of green house gases like

methane from landfills. To reduce our school’s impact on the Denver Arapahoe

Disposal Site (and in turn, the planet), we must learn to recycle and compost

more while throwing away trash less. Unfortunately, this is much more difficult

than it would appear. More often than not, a recyclable or compostable material

ends up being wasted by being thrown in the trash or a single piece of trash

ends up in the recycling or compost, contaminating all reusable goods inside. If someone is uninformed enough to not know where a

certain item goes, we would rather they throw away a recyclable or compostable

item in the trash, wasting only one item’s reusability, than throw away

something non-recycle or non-compostable in the wrong bin, wasting numerous

item’s reusability.

This

issue has many underlying reasons. For one, people simply lack the education

about what’s trash, what isn’t and in which bin it belongs. Secondly, there is

limited access to recycling and compost bins and an excess of trash bins.

Combined with the third reason, a lack of initiative, people are lead to simply

throw away their recyclable or compostable materials in the trash simply

because its more convenient. For instance, not many people will walk out of

their way to ensure that their compostable coffee cup makes it into the compost

if they only have 10 minutes in between classes when the only bins nearby are

for trash. However, as Al Gore argues, if there was ever a time to care and

have a sense of urgency about our planet, it would be now.

Beginning our Investigation:

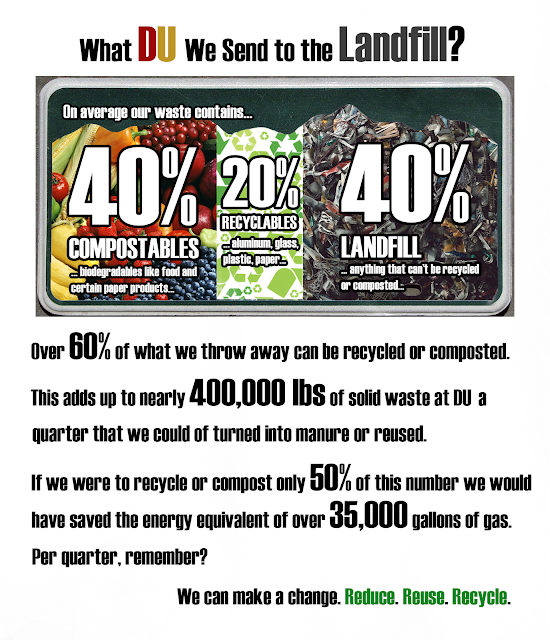

Our investigation began with our class’s

participation in a trash audit. From October 8-11 we took apart and sorted

through 57 bags of trash and recycling from 4 sites, Johnson-MacFarlane

Halls, Nagel and Nelson, and the outside trash and recycling bins. We

calculated that, on average, each bag contained 39% trash that would go to the

landfill, 21% recyclable material and 40% compostable material. Although these

numbers may seem promising, here’s the catch: nearly all of these bags were

contaminated. That 61% recyclable and compostable material is essentially

useless. Unless someone is physically going through each bag, separating the

trash from the recyclable from the compost, all of the reusable materials are

sent to the landfill anyway. This part of our investigation alone has lead us

to our thesis.

Forming our Solution for

Change:

As

Orr quoted Wiesel in his book Earth In Mind, the problem with education is that “[i]t emphasizes theories instead of values, concepts

rather than human beings, abstraction rather than consciousness, answers

instead of questions, ideology and efficiency rather than conscience” (8). The

first step in our solution for change is just that, an education that focuses

realistic and practical applications of our knowledge of trash.

During

orientation week, we were required to attend at least 3 meetings about drug and

alcohol use, nearly all of which overlapped in content and became redundant. I

propose that we allot one of those blocks of time, or even create a new one,

for a mandatory seminar on trash. People will be shown exactly what is

considered trash, recycling and compost and exactly where they belong to be

thrown away.

The

educational seminar during orientation week will surely hit home for a few days

or two, but after some time people will lose interest or simply forget what

they’ve been taught. Additionally, as Robin Nagle puts it, one of the larger

problems with trash is that it “is generally overlooked because we create so

much of it so casually and so constantly that it’s a little bit like paying

attention to, I don’t know, to your spit, or something else you just don’t

think about.” As such, our second solution is visibility and prevalence. If

each dining hall were to have their own weekly trash report, containing

information regarding how much was composted and how much was thrown away,

people may begin to realize the impact they have and make healthier decisions.

Additionally, there needs to be a greater access to the variety of bins. Each

trash bin outside consists of 50% trash, and 50% recycling and compost. Rather

than spend $1000 to buy a new trash or recycling bin, how about we turn all for

one into one for all? The circular bin can physically divided into three

labeled and color-coded parts with three separate trash bags: one for trash,

one of recycling and one for compost. That way, no matter where you are on

campus, if you see a trash bin, you also see one for recycling and one for

compost.

Just

like you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, you can place

all the right tools in the hands of our community’s members, but you can’t

ensure that they’ll use them properly. It’s impossible to guarantee that every

single person at DU will throw away their trash, recyclables and compost in the

proper bin 100% of the time but what we can do is reduce the chance that they

will. With improved education, visibility and prevalence we believe that we are

doing as much as we can to reduce the margin of error, putting only a

manageable, yet necessary fraction of responsibility into the hands of our

fellow peers.

I.

Orr, David.

"Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect.” Earth

in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect: David W. Orr:

9781559632959: Amazon.com: Books. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2012.

II.

Gore, Al. "On

Katrina, Global Warming." On

Katrina, Global Warming.

N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2012. <http://www.commondreams.org/views05/0912-32.htm>.

III.

"The Believer

- Interview with Robin Nagle." The

Believer. The Believer,

n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2012.

<http://believermag.com/issues/201009/?read=interview_nagle>.